Animal Reservoirs and COVID-19 Variants

January 31, 2022

By Ryan M. Thomas

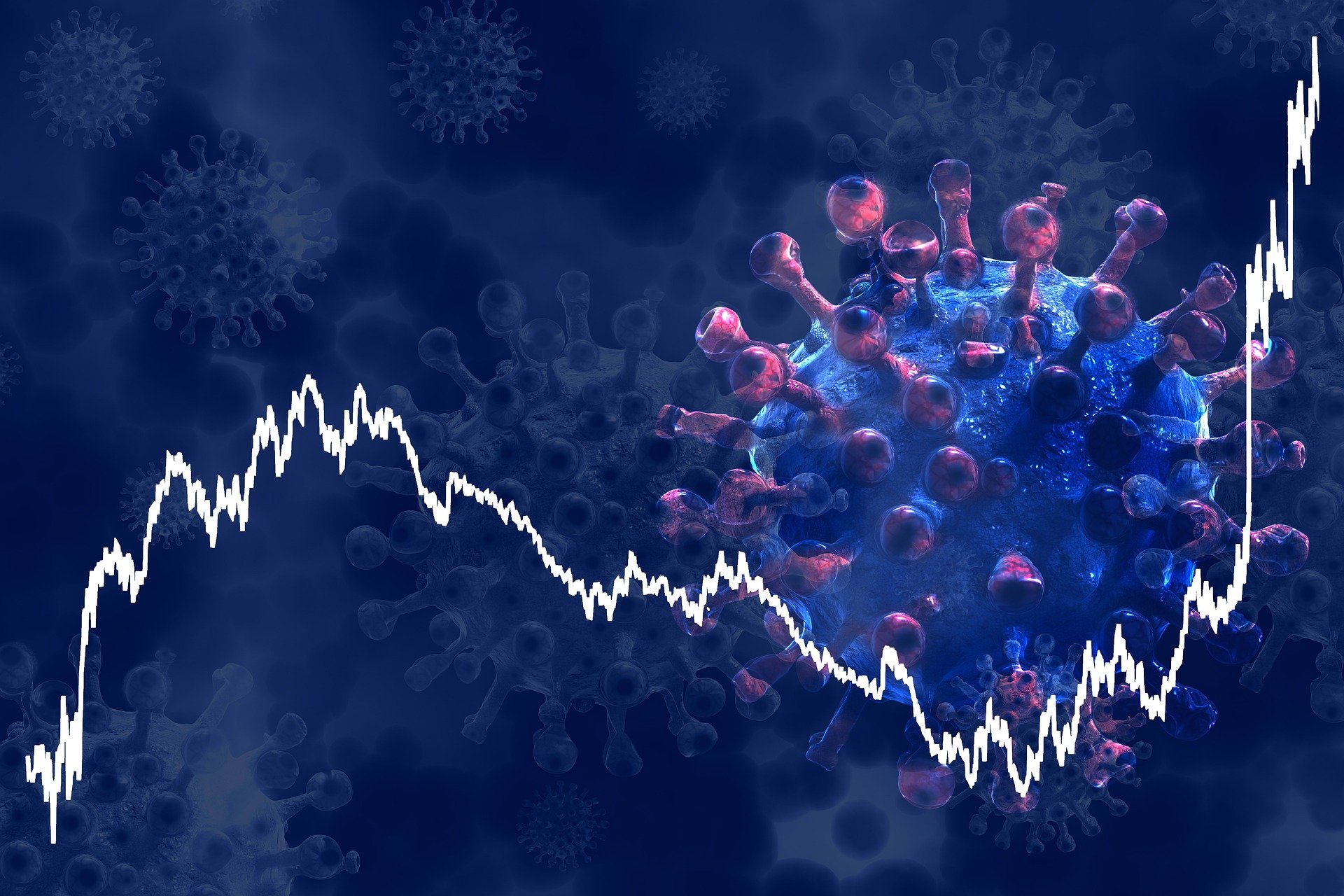

Last month, we pondered what the world would be like with 5-10% of the population sick. Today, we know: it has resulted in the shortage of rapid tests, thousands of cancelled flights, overwhelmed hospitals, and sick first responders being asked to return to work sooner—even with mild symptoms. It has also caused further supply chain crunches, but also a growing distrust of government and the ability for first-generation vaccines to end the pandemic.

As the Omicron wave passes, some of those that predicted that Omicron would be the last wave are now abandoning their optimism. Increasingly, scientists are accepting that COVID-19 is not disappearing because of this wave, or the next wave, and that herd immunity cannot be achieved by the widespread adoption of a non-sterilizing vaccine alone.

In this month’s newsletter, I’d like to highlight one of the reasons we believe that COVID-19 will not go quietly into the night: animals – reservoirs for new variants.

What are variants?

All viruses evolve, mutate, and change in size and shape over time. The higher the transmission rate, the more a virus replicates, and the greater the chances that the construction of the genome obtains an error, which defines a mutation. Mutations of a virus can potentially aid the virus in avoiding our immune system’s defences (and vaccine immunity). When a virus mutates, the changes may be small and insignificant, but in some cases, the mutations can be more significant and may affect the virus’s ability to infect us and cause more severe symptoms. Significant mutations can be identified when a virus changes in size, shape, and functionality, thus affecting its binding affinity to our cells.

Virus mutations may either be helpful or harmful to the virus’s ability to spread and infect more hosts. Through a process of natural selection, the most robust version of the virus emerges where variants that weaken the virus die off.

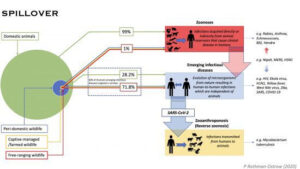

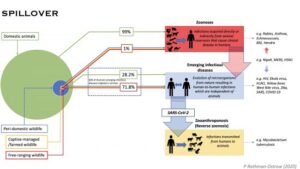

Spillover

Although rare, viruses can move from one species to another. This is called a spillover event.

Spillover events require a virus to overcome several obstacles to become feasible in another species. Most spillover events follow the same process: the virus cannot become too effective in infecting and killing its primary host species, because that would ruin the species’ viability—and this species acts as a reservoir for the virus.

A spillover event requires close contact between the primary host species and the secondary host species. The transmission also requires the virus to break through obstacles that would typically prevent spillover events—this includes circumventing the inherent incompatibility between the virus and its new species and overcoming the new host’s immune response.

Throughout the pandemic, we’ve seen several instances of spillover from humans to other species:

- Covid is rampant among deer, research shows

- Hong Kong will cull 2,000 small animals after several hamsters test positive for COVID-19

Spillback

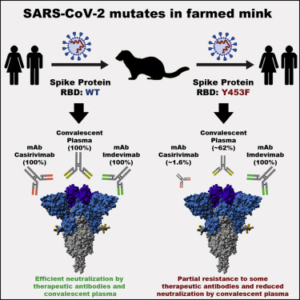

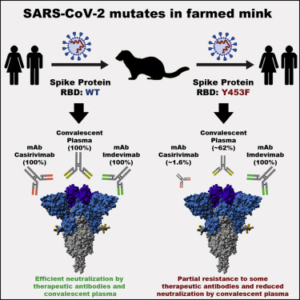

Once a spillover event occurs, a spillback event becomes possible. This is when the virus moves back into the original host species. Often this event allows for the virus to mutate significantly, evading both natural and vaccine-induced immunity.

COVID-19’s ability to spillback was identified early in the pandemic when Denmark sacrificed over 17 million mink.

For those of you who would like to read further into the science, please consult this paper from Science:

Animal reservoirs

Spillover and spillback events are a reminder that our health is intertwined with that of animals. As COVID-19 has proven the ability to move between species, it is also creating reservoirs, or opportunities, for mutation and the creation of new variants.

Natural immunity from previous infection has proven to be short-lived, with ⅔ of people infected with Omicron saying that they were previously infected. Additionally, first-generation vaccines are now only about 30-40% effective in preventing infection and for shorter periods, now weeks instead of months.

Animal reservoirs will allow COVID-19 to survive without human hosts. This concerning fact now sets the stage for the independent evolution of SARS-CoV-2 with spillback events causing unpredictable infectivity and fatality rates.

Pandemic implications

Under conditions in which a virus only infects a single host species, an outbreak can spread throughout a population and then fade when hosts either develop immunity or die off from infection. The outbreak’s trajectory changes when the virus is a generalist and is capable of infecting multiple host species, creating reservoir hosts.

Reservoir hosts can then facilitate viral evolution and advance lineages with increased virulence for the original host species. Since many animal species already harbour many different coronaviruses, this may allow COVID-19 to recombine and acquire or evolve and obtain new traits like increased virulence, transmissibility, pathogenicity and immune evasion from prior infection or vaccines.

Conclusion

It doesn’t appear that COVID-19 is disappearing anytime soon. Since the beginning of the pandemic, we’ve maintained the thesis that this would not be a short pandemic. COVID waves and surges will continue, some may be milder than others, and some may be much worse than what we’ve already experienced. The need for a pan-coronavirus vaccine – one that not only protects against COVID-19 and current variants, but also against other coronaviruses – is not going away, and if anything, has begun to be embraced as the only exit strategy for this pandemic.

Animal Reservoirs and COVID-19 Variants

January 31, 2022

By Ryan M. Thomas

Last month, we pondered what the world would be like with 5-10% of the population sick. Today, we know: it has resulted in the shortage of rapid tests, thousands of cancelled flights, overwhelmed hospitals, and sick first responders being asked to return to work sooner—even with mild symptoms. It has also caused further supply chain crunches, but also a growing distrust of government and the ability for first-generation vaccines to end the pandemic.

As the Omicron wave passes, some of those that predicted that Omicron would be the last wave are now abandoning their optimism. Increasingly, scientists are accepting that COVID-19 is not disappearing because of this wave, or the next wave, and that herd immunity cannot be achieved by the widespread adoption of a non-sterilizing vaccine alone.

In this month’s newsletter, I’d like to highlight one of the reasons we believe that COVID-19 will not go quietly into the night: animals – reservoirs for new variants.

What are variants?

All viruses evolve, mutate, and change in size and shape over time. The higher the transmission rate, the more a virus replicates, and the greater the chances that the construction of the genome obtains an error, which defines a mutation. Mutations of a virus can potentially aid the virus in avoiding our immune system’s defences (and vaccine immunity). When a virus mutates, the changes may be small and insignificant, but in some cases, the mutations can be more significant and may affect the virus’s ability to infect us and cause more severe symptoms. Significant mutations can be identified when a virus changes in size, shape, and functionality, thus affecting its binding affinity to our cells.

Virus mutations may either be helpful or harmful to the virus’s ability to spread and infect more hosts. Through a process of natural selection, the most robust version of the virus emerges where variants that weaken the virus die off.

Spillover

Although rare, viruses can move from one species to another. This is called a spillover event.

Spillover events require a virus to overcome several obstacles to become feasible in another species. Most spillover events follow the same process: the virus cannot become too effective in infecting and killing its primary host species, because that would ruin the species’ viability—and this species acts as a reservoir for the virus.

A spillover event requires close contact between the primary host species and the secondary host species. The transmission also requires the virus to break through obstacles that would typically prevent spillover events—this includes circumventing the inherent incompatibility between the virus and its new species and overcoming the new host’s immune response.

Throughout the pandemic, we’ve seen several instances of spillover from humans to other species:

- Covid is rampant among deer, research shows

- Hong Kong will cull 2,000 small animals after several hamsters test positive for COVID-19

Spillback

Once a spillover event occurs, a spillback event becomes possible. This is when the virus moves back into the original host species. Often this event allows for the virus to mutate significantly, evading both natural and vaccine-induced immunity.

COVID-19’s ability to spillback was identified early in the pandemic when Denmark sacrificed over 17 million mink.

For those of you who would like to read further into the science, please consult this paper from Science:

Animal reservoirs

Spillover and spillback events are a reminder that our health is intertwined with that of animals. As COVID-19 has proven the ability to move between species, it is also creating reservoirs, or opportunities, for mutation and the creation of new variants.

Natural immunity from previous infection has proven to be short-lived, with ⅔ of people infected with Omicron saying that they were previously infected. Additionally, first-generation vaccines are now only about 30-40% effective in preventing infection and for shorter periods, now weeks instead of months.

Animal reservoirs will allow COVID-19 to survive without human hosts. This concerning fact now sets the stage for the independent evolution of SARS-CoV-2 with spillback events causing unpredictable infectivity and fatality rates.

Pandemic implications

Under conditions in which a virus only infects a single host species, an outbreak can spread throughout a population and then fade when hosts either develop immunity or die off from infection. The outbreak’s trajectory changes when the virus is a generalist and is capable of infecting multiple host species, creating reservoir hosts.

Reservoir hosts can then facilitate viral evolution and advance lineages with increased virulence for the original host species. Since many animal species already harbour many different coronaviruses, this may allow COVID-19 to recombine and acquire or evolve and obtain new traits like increased virulence, transmissibility, pathogenicity and immune evasion from prior infection or vaccines.

Conclusion

It doesn’t appear that COVID-19 is disappearing anytime soon. Since the beginning of the pandemic, we’ve maintained the thesis that this would not be a short pandemic. COVID waves and surges will continue, some may be milder than others, and some may be much worse than what we’ve already experienced. The need for a pan-coronavirus vaccine – one that not only protects against COVID-19 and current variants, but also against other coronaviruses – is not going away, and if anything, has begun to be embraced as the only exit strategy for this pandemic.